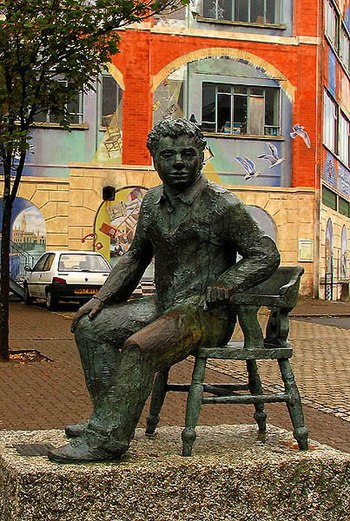

If you search and find a poetry workshop near you, I hope you can go into it, not gently, but with the passion of Dylan Thomas, who wrote for his blind, dying father the poem on which the title of this post is based. And if you think that’s cheesy, well, I hope you’ll forgive me for the video below, by the actors from the movie Interstellar (2014), starting with John Lithgow.

I wish I could have found a full version with the mellifluous voice of Michael Caine. His delivery is perfection, not too emotional, yet not wooden. You can hear part of it in the movie’s trailer (starting at about 1:43) right here.

But then again, I haven’t seen the movie yet, and maybe he doesn’t recite the entire thing? Still, his as well as this combined reading, I think, is more effective than the slowly dramatic presentation by Anthony Hopkins, or even the grandiloquent delivery by Dylan Thomas himself, though I admit his voice was gorgeous. Okay, okay, that’s just my humble opinion. I just know the danger of letting too much sentimentality into my voice during my own readings. It can make the listener uncomfortable, and distract from the words themselves. I think it’s a struggle for most readers to find a balance between reading it like you mean it and going too far. A reading should never be robotically monotone, but neither should it be silly, or make the reader seem full of herself/himself.

Workshop

But we were talking workshops. The members of the Cross Keys Poetry Society have elected to move into workshop mode, and it’s all very exciting. We developed some “rules,” guidelines really, based on ones like these, edited with the author’s permission, to fit our group’s needs.

And so what does Dylan Thomas’s poem have to do with this? Well, the group had expressed unanimous interest in exercises and work-shopping in order to help each other to improve and polish our work. They were particularly interested in dabbling in poetic forms. Since we delved into the sonnet already (It seems I haven’t blogged about that yet, so perhaps I’ll come back to it here in a later post), we decided to tackle the French form called the villanelle.

“Do Not Go Gentle Into that Goodnight,” by Dylan Thomas

Though first published in 1937, this villanelle has the style, diction, and tone of a much older poem, especially to Americans who are used to the often more casual speech of modern poetry. It strictly follows the villanelle form, and for the most part feels altogether traditional. All the lines but three are end-stopped, completing their syntactic sense and set off by punctuation at their rhymed conclusions. The first and third lines, which are repeated in pre-determined spots throughout the poem, remain exactly the same each time. This makes it a perfect pattern to follow if one wants to stick rigidly to the villanelle form. Even Poets.org uses it as the prime example.

But I am getting ahead of myself here. Where can we find an easy-to-follow guide on how to write a villanelle? I asked myself, and went searching the great and mighty Google. What I found delighted me. Fellow blogger and poet, Karin Gustafason, aka ManicDdaily, has a rather fun but complete rundown in a post she made in 2009, including a helpful outline of the pattern. This, minus asides of the day regarding the US President and other non-related tidbits, is what I used to explain it to the group. Here’s a brief excerpt:

The most important tip I can give to anyone writing any formal verse is to feel free to cheat. For example, if rhyme is required, don’t worry about not being able to come up with perfect ones. Use “almost rhymes” or “slant rhymes” (that is, “not quite rhymes”). Besides giving you more words to choose from, this will keep the poem from being so sing-songy.

If repeated lines are called for, as in the case of the villanelle, don’t worry if you have to vary them a bit, that is, if your repeating lines don’t in fact exactly repeat. Remember that meaning always trumps form.

It’s helpful to think of the form as a kind of a map, a means to music. It’s useful to have all the streets laid out, but occasionally, when you want your poem to actually reach a destination, you have to cut through some back yards.

Of course, Kristine also goes on to say, “you can’t cheat till you know the rules.” So she follows with really the best delivery of the basics that I could find online. Make sure you read them! And check out the posts just before and after for more examples and fun commentary.

So we have a metered, usually iambic, poem with these features:

- 19 lines, divided into 6 stanzas.

- The first 5 are tercets (3 lines).

- The last is a quatrain (4 lines),

- concluding with a couplet consisting of the repetition of lines 1 and 3.

- Line 1 is repeated in lines 6, 12, and 18.

- Line 3 is repeated in lines 9, 15, and 19.

- There are only 2 rhyming sounds (A and B).

- The 1st 5 stanzas rhyme ABA.

- The last stanza rhymes ABAA.

Oh, but friends, it sounds so much more complex than it really is. I have read even scholars who claim that the form is a nightmare to write–nonsense! Don’t let them discourage you. It’s actually a lot of fun, and since some of the lines repeat, and tone is cyclical, the poem can be a fun discovery, and sometimes it can almost write itself once it picks up momentum.

To write a villanelle, you should find one that you like and look at it closely. Ask yourself why you like it so much, and then pattern your own creation after it. Keep in mind, in this stage of the workshop we are only doing an exercise, not creating a Mona Lisa. Allow yourself to play; it’s the best way to learn.

Now, as for that cheating Karin mentioned–I passed out two other examples of villanelles, one that strays slightly from the exactitude of the form, and one that deviates wildly.

Read “The Waking,” by Theodore Roethke.

This one came a bit later than Dylan’s “Good Night,” published in 1953. Yet it still mostly follows the dictates of the form very closely. However, there are a few interesting variations that move the poem along rather nicely. Dylan’s poem with its precise repetition feels like a hopeless round-about from which there is no exit. That ominous feel is part of what makes it so incredible.

In contrast this poem, with it’s slight variations, evokes a subtle feeling of hopefulness, a sense that one could let loose from the circling loop and be set flying in a new arc.

Opening Lines:

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

There is still that cyclical effect, but along with Roethke’s choice of diction, and ambiguity there is a more dream-like quality to this poem. That first line repeats exactly as it is ordained to do in lines 9, 15 and 19. But the third line loosens ever so slightly in line 9 by substituting “and” for I. Then it drifts out a bit further by inserting the word “lovely” in “And lovely learn by going where I have to go.”

It works like a fresh intake of breath, a light, brief break from the cycle before it comes back home and to a conclusion that feels satisfying, rather than doomed, in line 19 where the original wording of line three is again repeated exactly.

Another device that Roethke uses to create more lift is that the intial (B) rhyme sound of lines 2 and 5 changes from “fear” and “ear” to the subtly altered “there, stair” and “air,” before returning to the original sound in the final stanza with the word “near.” It’s like a bit of poetic slight of hand that keeps you in the form’s circle while lifting you out of your seat just enough to see the scenery outside before setting you lightly back down.

Similarly the initial rhyme sound (A) of “go” becomes the very off-rhymed “how” in line ten, nearly halfway through the cycle of the piece. Of course this may all depend on what the individual reader’s accent does with those sounds.

Finally let’s read my favorite villanelle, and one of my favorite poems of all time:

Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art.”

Bishop’s villanelle strays widely from the strict path in some truly splendid ways. It works in such a way as to smooth out the rolling ride of the form’s repetition while still maintaining its essential form and flow.

Published in 1979 it is more modern in diction and line structure. Many of the lines, like 2 and 3, are enjambed, or run-on lines, in which the syntactic sense is not interrupted by the rhyme at the end, but rather continues on into the next line.

Opening Lines:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;so many things seem filled with the intentto be lost that their loss is no disaster.

In this version line one remains the same each time it is repeated until it doubts its own repeated assertion in its final appearance in the ending couplet: “the art of losing’s not too hard to master.”

But line three, the other line decreed to repeat in fact only repeats its final word, “disaster.” Line 9, 15 and 19 are all completely different except for that word, yet they are similar enough that its use unifies them.

Like Roethke, Bishop uses slant rhymes for variation–fluster with master and gesture. And then there is the delightful “last, or” in

I lost my mother’s watch. And look! my last, ornext-to-last, of three loved houses went.The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

The combination elevates the form into something new, refreshing, rather than betraying it. These alterations help it reach more of a conclusion, I hate the word closure–catharsis maybe–in the final lines when the speaker reveals her greatest loss, “even losing you. . . ”

Well, if you skipped, you had better go back and read it. It truly is one of the most marvelously crafted and creative modern uses of traditional form.

Your Turn

So why are you still reading this? Go off and do this on your own. Exercise is much more fun than reading about exercise. Pick one of the many examples linked to in this article and push off. And most importantly, have fun with it.

And if you just so happen to reside in central Pennsylvania, I would be gobsmacked and tickled if you could join us at the Priestley-Forsyth Memorial Library next Tuesday, the third of February at 7:00 pm. I know we are all terribly busy people, but at the very least you should prod yourself to come up with the opening three lines by then. And anyway once you do, your villanelle is likely to surprise you as it starts rolling down hill of its own volition.

If you absolutely cannot join us in person, please post your efforts here in the comments below this post. I cannot wait to see what you do.

I leave you with this one last bit of inspiration, the video I referred to at the beginning, from the movie that came out this last November. Enjoy–and then go forth and write!

Hey David–thanks for the mention. I am inspired to think of villanelles–I used to write them fairly often, but haven’t for a while. I’m going to be thinking of one! Take care, k.

LikeLike

Yes! Glad I could help! And I truly was tickled to find your post on my search. I believe you were fourth or fifth on my search page when I entered “How to write a villanelle.” 😀 Thanks for your help with this!

LikeLike

That is very funny. I wrote a few about it–one about layering like banana pudding. I also did a little children’s story villain=elle you might like. https://manicddaily.wordpress.com/2011/12/22/contrastvillanellesvillain-elle-with-watercolors-and-elephants/

I should probably delete all the political stuff from the other–it was rather casually written, but it is a pretty fully guide. I used to write them a great deal. Take care and thanks again. k.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very fine post David…glad to see you back.

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Charles! Good to be at it again.

LikeLike

Ha!

LikeLike