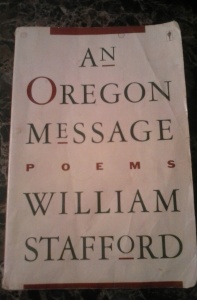

It was in September of 1987 that William Stafford’s little book, An Oregon Message was first published. So with the authority not even vested in me, I have proclaimed this William Stafford Weekend, and it shall be evermore known as thus. Well, if you promise not to forget.

Check out Saturday’s post to follow all the links to more of Stafford’s written words, as well as his videos and audio recordings. And if you’ve been hanging around the Dad Poet blog for any length of time you know that Stafford is, as our American Vice President might say, a “BFD” for me. I’ve written about him here no less than 17 times, and most often those posts included bits from my Soundcloud or YouTube channels.

Also, if you love Stafford, make sure you get a copy of this book while there are still a few new, but mostly used, copies of it available. Of course, if Amazon can get it, there’s a good chance your local bookstore can order it in for you too, and if you just have too many books on your shelf, be sure to ask your local library if they have a copy or can get it for you. Lots of libraries participate in inter-library loan programs and can get you a borrowed copy of almost anything.

I’ve noticed in book reviews, both the stodgy, official ones, as well as the casual “Good Reads” type of recommendations, people are fond of quoting from his introduction, “Some Notes on Writing.” In fact, I’ve noticed that they often quote from this one-half page before they quote from one of the poems in the rest of the book, almost as if they don’t know what to make of them, and don’t know how to recommend them without this explanation.

My poems are organically grown, and it is my habit to allow language its own freedom and confidence. The results will sometimes bewilder conservative readers and hearers, especially those who try to control all emergent elements in discourse for the service of predetermined ends.

Each poem is a miracle that has been invited to happen. But these words, after they come, you look at what’s there. Why these? Why not some calculated careful contenders? Because these chosen ones must survive as they were made, by the reckless impulse of a fallible but susceptible person. I must be willingly fallible in order to deserve a place in the realm where miracles happen.

Writing poems is living in that realm. Each poem is a gift, a surprise that emerges as itself and is only later subjected to order and evaluation.

–William Stafford

Please understand that I ask this as one of William Stafford’s biggest fans; why is it that people quote poets as if they are quoting historians and court stenographers? He appears simple, yes, but if that’s all you see when you read Stafford, you haven’t read much of him. As my ex-mother-in-law used to say of her quiet husband, “Still waters run deep.” So maybe we should be careful taking just a statement or two out of his introduction page and using it to say that Stafford was “uncomplicated,” or that he never edited, revised, or polished his poems. Read that last sentence of his again. Did he really say that?

What he’s saying is that for him writing poetry is a process, and he doesn’t get in the way of the process. In his article, “A Way of Writing,” a very short but fascinating read which I highly recommend, he says:

So, receptive, careless of failure, I spin out things on the page. And a wonderful freedom comes. If something occurs to me, it is all right to accept it. It has one justification: it occurs to me. No one else can guide me. I must follow my own weak, wandering, diffident impulses.

A strange bonus happens. At times, without my insisting on it, my writings become coherent; the successive elements that occur to me are clearly related. They lead by themselves to new connections. Sometimes the language, even the syllables that happen along, may start a trend. Sometimes the materials alert me to something waiting in my mind, ready for sustained attention. At such times, I allow myself to be eloquent, or intentional, or for great swoops (Treacherous! Not to be trusted!) reasonable. But I do not insist on any of that; for I know that back of my activity there will be the coherence of my self, and that indulgence of my impulses will bring recurrent patterns and meanings again.

He is talking about the creative process of a highly practiced writer who allows anything that comes to mind to land on paper without judgment. In this way, writing becomes discovering. But he does not say that he does not later give the better discoveries a bit of polish. In fact, he does indicate in the first quote above, from An Oregon Message, that after the poem emerges “as itself,” it is “later subjected to order and evaluation.”

So I submit to you, my young poet friends, those of you who believe that what pours out of you is sacred and unalterable on the first go, that this is not at all Stafford’s practice or belief. It is no more true than when Bukowski says, “if it doesn’t come roaring out of you, don’t do it,” that he actually means to say that he doesn’t go back and tidy up the best of what has been roared before it is read by the public. If you believe that Walt Whitman truly wrote down and presented to us each “barbaric yawp,” without carefully adjusting how it would appear on the line, you understand precious little about the performers that were Whitman and Bukowski. Whitman spent most of his life rewriting Leaves of Grass.

Stafford does confess, albeit ever-so-briefly, that he does some of this evaluating himself. The key to understanding what he’s talking about is knowing that he wrote and tossed out probably uncountable reams and notebooks full of first attempts that you and I will never see. In “A Way of Writing” he makes this confession:

. . . most of what I write, like most of what I say in casual conversation, will not amount to much. Even I will realize, and even at the time, that it is not negotiable. It will be like practice. In conversation I allow myself random remarks–in fact, as I recall, that is the way I learned to talk–so in writing I launch many expendable efforts. A result of this free way of writing is that I am not writing for others, mostly; they will not see the product at all unless the activity eventuates in something that later appears to be worthy.

Granted, he probably did a lot less revising than you or I, but only because he was always and daily in writing mode. I remember, in an interview with the Paris Review Billy Collins saying “I don’t revise very much.” I think in a different interview he indicated that he considers his work, after the initial creation of a piece, to be editing, rather than revision, because revision involves re-imagining an entire project differently, whereas, what he does is to hone and perfect the best of what has been created. And what if his creation doesn’t come together in at least some rough form in one sitting? “I pitch it,” he says.”

This is easier to do, perhaps in a short form like poetry, especially if you write a lot and throw away a lot. It reminds me of how some basketball players actually miss more baskets than they make, but they break records because they just keep tossing the ball. I think this is probably closer to what Stafford’s process was, although he was perhaps less than forthcoming about the details.

And finally, if you still think the man was simple, and just wrote whatever came to mind, and that what we have read of his is exactly as it first was written, then please go read the title poem of the collection, or better yet, go back and digest “A Ritual to Read to Each Other,” and kindly explain to me what kind of super human could create such dense and beautiful metaphoric work without some serious time and effort, molding his words into the final product before it was published. I simply cannot imagine it.

Remember, these guys are poets, and poets can’t always to be trusted to give all the facts when they talk about the truth.

Today’s two poems, like yesterday’s are also from An Oregon Message, and while they are less intricate than poems like “Ritual,” they are none the less, minor works of genius. I know, I know. Stafford would argue with that statement, but I’ll stop talking now, and just let his poems speak for themselves.

I have never written a poem that was fully formed at the first draft. Self-editing is the essence of good writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely.

LikeLike

Funny thing, I just noticed that last weekend when I posted this, I said, “BFG” instead of “BFD.” Sigh, talk about the need to self-edit! The damned subconscious influence of Disney movies!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We all understood nonetheless.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The editor needs an editor for his blog. 🙂

LikeLike

I posted a wonderful story about Stafford.

https://briandeanpowers.wordpress.com/2016/08/29/william-stafford-on-writing/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading now! I don’t know how I missed this!

LikeLike